Deborah

Natsios "National Security SPRAWL: Washington DC" |

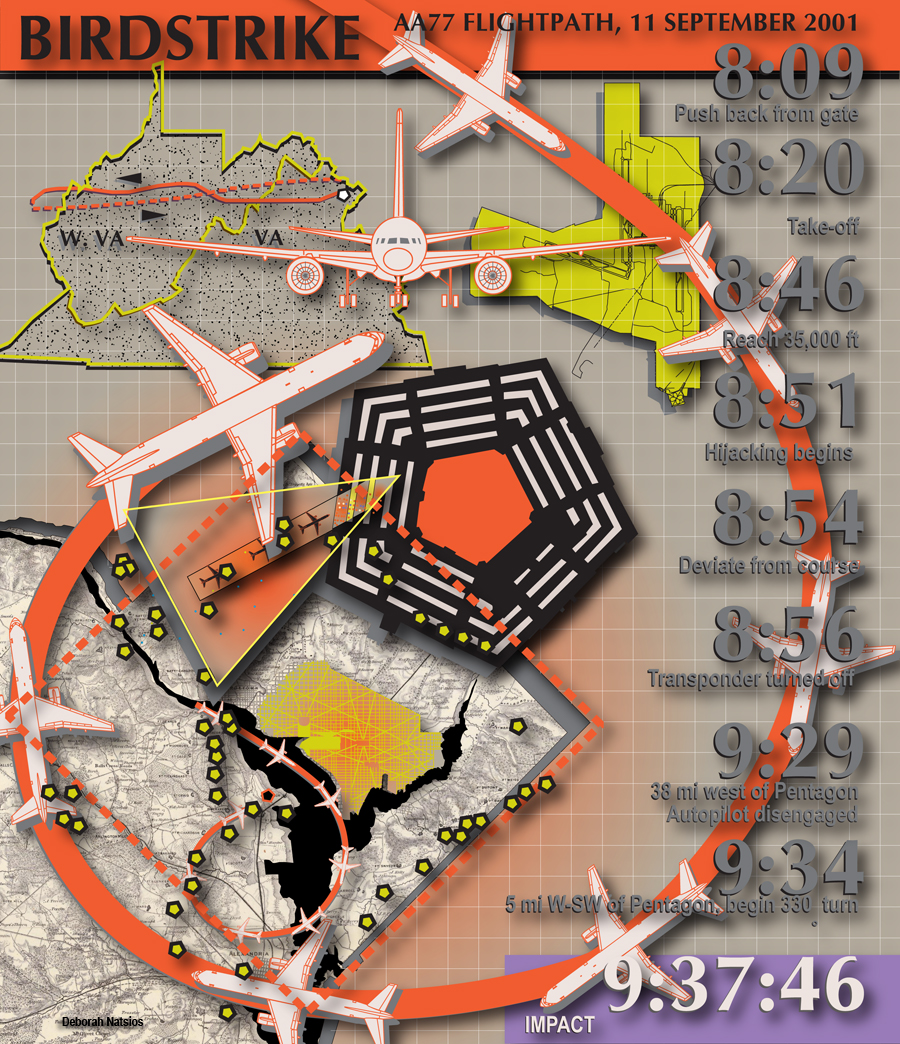

Birdstrike

Greater Washington DC's airspace offers strategic overviews of tangled metropolitan landscapes shaped by the exigencies of successive national security paradigms. In the hour before it crashed into the west facade of the Pentagon at 9:38AM on 11 September 2001, hijacked American Airlines flight 77 mapped a provocative trajectory above this complex domain, tracking national security landmarks embedded in one of the nation's fastest-growing urbanised formations 1. Within the hour, the capital region's snarled American-dream sprawl would be transformed into the unprecedented threatscape of the 'homeland'.

The Los Angeles-bound flight had headed west from suburban Dulles International Airport before stealthily doubling back towards the capital city with transponder deactived 2, navigating a final overflight of Northern Virginia's anarchic exurban terrain. Beneath the opportunistic flightpath, national security institutions and defence contractors lay discreetly camouflaged within a congested topography of subdivisions, big-box retailers, cineplexes, regional malls and information technology hubs.

At Dulles' southern perimeter, in Chantilly, Virginia, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) - maker of the country's classified spy satellites - huddled in a once-clandestine $350-million suburban headquarters 3. The NRO shared a paradigmatic suburban enclave with its top contractors - including Aerospace Corporation, Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin - the pastoral embellishments of an 'exclusive master-planned business community with state-of-the-art business setting amidst an environment with expansive green spaces, parks, ponds and trails' 4 . Closer to the Pentagon, in Langley, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) - developer of CORONA 5, the nation's first photoreconnaissance satellite system - was sequestered in a complex modelled on an academic campus prototype. Surrounded by evocatively seigneurial neighborhoods - Savile Manor, Downcrest and Rokeby Farm - the CIA had taken refuge in suburban standards that codified the spatial and functional isolation of properties. Free-standing structures set back on greenscaped lots invited convenient anonymity rather than interaction.

Guided by a bird's-eye view of autumnal landscapes and glinting Potomac River wending below, hijackers manoeuvred the Boeing 767 towards the pentagonal fortress at the margins of the capital's exemplary geometries. In the last minutes of flight, a catastrophic earthbound spiral from an altitude of 7,000 feet collapsed institutional distinctions that stubbornly segregated aerial from terrestrial intelligence collection - as reconnaissance's privileged eye-in-the-sky was crushed into the object of its predatory scrutiny. (fig. 1)

Long before Flight 77 tracked Northern Virginia's defence topography, the region was first surveyed by air in 1861 when a Union balloon hovering near Arlington helped orchestrate a successful attack against Confederate troops 6. In intervening years, aerial and satellite technologies imaged the region's unruly growth for civilian applications, informing contentious processes of regional planning, traffic analysis and environmental evaluation. After 11 September, Greater Washington would submit to a new generation of 'persistent surveillance', including the military's experimental use of sensor-equipped blimps for aerial command-and-control 7.

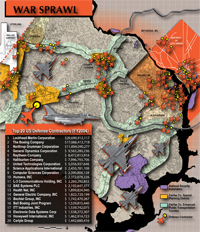

War Sprawl

The Department of Defense bulwark targeted on September 11 had provided the principal gateway for Northern Virginia's defence development on its completion in 1943, attracting dense clusters of contractors to its perimeter in Arlington County. These included the hijacked aircraft's own manufacturer, the Boeing Corporation, which, with contracts totaling $13.3 billion, was the nation's second-ranked vendor in 2001 8 . (fig. 2)

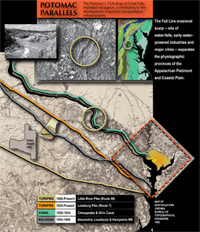

Expansion of Greater Washington's government bureaucracies and technocracies, of regional infrastructures, settlements and population had accelerated with security crises 9 from the Civil War through the two World Wars, the Korean conflict, Cold War, Vietnam and current Middle East campaigns. Defence installations and symbiotic contractors would become a mainstay of the area's economy. By 2004, TRW, Raytheon, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and DynCorp alone employed more than 100,000 workers around the region 10 . Spurred by government-related employment - much of it linked to the national security sector - Greater Washington had by 2001 evolved into a mostly suburban metropolitan formation of 6,000 square miles with a population approaching 6,000,000 11. (fig. 3)

At the height of the Cold War, defence development invaded Fairfax County with the completion of Dulles International Airport (1962), the National Defense Highway System's circumferential Capital Beltway (1964) - its diameter calculated to exceed a thermonuclear detonation centered on the capital - and new CIA headquarters (1962) (fig. 4).Anticipating unprecedented scales of consumerism, another 1960s landmark emerged minutes from the CIA. At the nexus of the emerging car-culture - the confluence of the Beltway and three major highways - the country's first regional mega-mall was established at Tysons Corner. Within a generation, a new urbanised typology would accrete around the mall's core. The edge-city - a building pattern defined as having at least 5 million square feet leasable office space and at least 600,000 square feet leasable retail space - introduced a significant suburban phenomenon: more jobs than bedrooms 12. To

day, Tysons Corner's edge-city jobs include leading defence employers Raytheon, BAE Systems, DynCorp, Bechtel, Northrop Grumman and Science Applications International, who share real-estate with the 'largest mass of retail operations on the East Coast, after Manhattan's' 13. Puchasers of stand-off weapons, early-warning systems and hostile-artillery location systems can also shop at Banana Republic, Brooks Brothers and The Disney Store 14. The convergence of national security, transportation and consumer infrastructures was the defining armature of Northern Virginia's suburban expansion.

Miles from the Capital's triumphalist monuments and circumspect war memorials, artefacts of the national security infrastructure have been normalised within suburban landscapes. Civil War forts were absorbed into the capital's arcadian park system. The W-83 Nike missile launch facility became a neighbourhood landmark in Great Falls, Virginia. A microwave station of the U.S. Army Strategic Communications Command towers over the malls at Tysons Corner 15 (fig. 5, 6). If the District of Columbia was the emblematic centre of defence policy - the suburbs hosted the evolving war industry, a war machine banalized by the very real-estate market forces that were shaping the anonymous complexities of sprawl.

Home Invasion

The 11 September attack inaugurated a new chapter in a regional history that had seen metropolitan growth surge with evolving security paradigms. The landmarks of Pierre Charles L'Enfant's seminal Plan of 1791 - tangible symbols of democracy, national unity and power - were deemed vulnerable. The National Capital Planning Commission, overseer of urban design and preservation, introduced to the monumental core an aestheticised arsenal - hardened street furniture, bollards and plinth walls - to fortify building perimeters 16. Jersey barriers and reinforced planters frame the new blast-proof streetscape. Street and sidewalk closures limited public access to sensitive locations. Roadblocks and checkpoints challenged motorists and pedestrians. 'Flexibility and choice' are diminished in a city whose foundational masterplan promoted transparency, vision and access 17.

With the goal of safeguarding high-value targets of the capital's symbolic core, aggressive protocols were also deployed to manage the chaotic landscapes of the metropolitan periphery. The anarchic civilian geography of outlying suburbs would be subjected to provocative security interventions as sprawl's diffuse spaces were disciplined by the capital city's emerging technologies of political control. Invasive technologies threatened to perforate citizenship's privileged constitutional envelope 18, however, jeopardising legal protections surrounding the coveted emblem of individual rights: the single-family home on its consecrated plot of primal green.

Transgressive enforcement methodologies were exhibited on a cloudy morning in March 2002, when 150 heavily armed federal agents invaded Northern Virginia's fragmented sprawl. Fanning out across scattered settlements west of Washington DC and watershed landscapes south of the Potomac, they conducted raids on a dozen area residences, businesses and non-profit organizations 19 . Targeted sites included single-family homes and office buildings in Fairfax County, most clustered together conspicuously near Dulles Airport in the 'boom town' of Herndon, on the Loudoun County border. (fig. 7)

Acting on an alleged 'criminal conspiracy to provide material support to terrorist organizations by a group of Middle Eastern nationals living in Northern Virginia" 20, the Operation Green Quest task force, comprising US Customs Service, IRS, FBI and Secret Service, disrupted suburban equanimity as agents 'broke doors and locks, brandished guns, and used handcuffs while they ransacked homes and offices' 21.

A subversive community of co-conspirators had allegedly exploited sprawl's unruly dislocations, infiltrating Fairfax County's heterogeneous mix of mandarin power and common democratic culture, tainting the suburban refuge of manicured lawns, asphalt driveways and culs-de-sac that are home to a population of over 1,000,000. (fig. 8)The raids, and those that followed, signaled that Northern Virginia's swathe of Greater Washington DC sprawl - a rapidly evolving region shaped by the competing interests of homeowners, regional planners, developers, highway engineers and environmentalists - was being remapped under the new geography of national security threat (fig. 9). As they tracked allegedly illicit financial practices, federal agents plotted the contours of an improbable new battlefield along snarled transportation corridors and layers of impervious asphalt that had supplanted the region's wildlife habitats and agricultural greenfields.

Threatscape

Unfolding beyond the historic city's boundaries, Greater Washington - home to one of the nation's largest Muslim populations 22 - had been cast as a distinctive locus of 'homeland', the emerging nationalist project that is reclassifying civilian landscapes as threatscape's defensible space.

With shrewd nomenclature, homeland taxonomies idealise national landscapes to enlist public support for a campaign to design a geography of threat. Landscapes nostalgically extolled in 'land of the free, and home of the brave' support uncritical narratives of national origin, unity, continuity and destiny. In their invasive sweeps across Fairfax and Loudoun county sprawl, the authorities were constructing an incipient homeland cartography.

Homeland invokes both moral order and the spatial conditions of suburban settlement. The iconic diagram of home set within the land betrays the culture's predilection for pastoral rather than urban exemplars, privileging green lawns over city sidewalks. With most of Americans residing in suburbs 23, threats against this dominant environment command the public's attention as well as its acquiescence to government interventions.

Information Battlespace

During the Civil War, the Defenses of Washington (1862) - a circumferential ring of fortified installations - successfully safeguarded the vulnerable city. Since 11 September, 'next-generation' technologies are administering sprawl's unrestrained landscapes. Streets, sidewalks and back yards that shape the suburban imagination are being re-imaged in military-grade surveillance and satellite-based GPS. Constructed in real and near-real time, sprawl's unpredictable legacy of subdivisions, culs-de-sac, big-box retailers, parking lots, fast-food franchises and high-tech corridors are being reconceptualized as 'battlespace' 24, the multidimensional battlefield constructed by sensor and reporting technologies that conduct intelligence collection, surveillance and reconnaissance. Reconstituted in GIS scene mapping and mission planning softwares 25 - suburban sanctuaries are captive to command-and-control arsenals which have supplanted the omniscient bird's-eye overview.

New technologies reveal latent infrastructures of political control already embedded in suburban landscapes. They expose consumer-driven sprawl as uniquely manipulable information space (fig. 10). The single-family home is a rich lode of sensitive information about debt, cars, credit cards, banking, taxes, travel, school performance and medical history. Data mining's invasive pattern-recognition algorithms - developed from statistics, artificial intelligence and machine learning - scour massive databases on behalf of the government, seeking 'interesting knowledge' 26. Sprawl's complex information space has become captive to panoptic schemes of 'multiple cartographies of surveillance' 27.

Next-Generation Sprawl

National security expansion continues to shape Greater Washington DC sprawl. Stringent new security regulations adopted after 11 September - including 82-foot building setbacks as a precaution against truck bombs - will require as many as 50,000 Department of Defense personnel currently occupying some 8 million square feet of rented space in 140 Northern Virginia buildings to relocate to secure sites in outer suburbs beyond the Beltway 28. Defence contractors are expected to follow, a migration that could 'exacerbate the region's traffic, destabilize the real estate market and flood already crowded schools' 29 and 'increase suburban sprawl and frustrate "smart growth" efforts in urban areas'. 30

As sprawl landscapes are hardened behind barbwired buffer zones and government transparency reduced by dark tinted windows, the encroachment of the national security domain - often under cloak of secrecy - has consequences for civilian space and civil liberties. Information activists are harnessing new technologies to educate the public and reverse-engineer the panopticon effect. Web-based initiatives such as Cryptome [www.cryptome.org], GlobalSecurity [www.globalsecurity.org], the National Security Archive [www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/], the Federation of American Scientists [www.fas.org] and Memory Hole [www.thememoryhole.org], as well as online discussion forums, function as national security watchdogs. They offer powerful tools for public education - often in the face of government opposition. Information transparency is empowering the public with critical bird's-eye views of the homeland's contested battlespace.

fig.

1

fig.

2

fig.

3

fig.

4

fig.

5

fig.

6

fig.

7

fig.

8

fig.

9

fig.

10

+ + +

NOTES

1 Vera Cohn and Michael Laris, 'Metro Area Population Continues Upward Trend: Loudoun County Among Nation's Fastest Growing According to Census', Washington Post, 15 April 2005, A01; see www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A52779-2005Apr14.html.

2 The National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, The 911 Commission Report, Government Printing Office (Washington DC), 2004, pp 2-35; see www.9-11commission.gov/report/911Report.pdf.

3 Senate Amendment No. 2502: To Withold Funds Allocated for Construction of the Headquarters Buildings of the National Reconnaissance Office,' Congressional Record, 10 August 1994; see www.fas.org/irp/congress/1994_cr/s940810-dod-nro.htm.

4 Cassidy & Pinkard is the area's largest locally owned commercial real estate firm: 'Cassidy & Pinkard Arranges Sale of Corporate Point III in Westfields', www.cassidypinkard.com/wmspage.cfm?parm1=4365.

5 National Reconnaissance Office, 'Corona', www.nro.gov/corona/facts.html.

6

US Centennial of Flight Commission, 'Balloons in the American Civil War',

www.centennialofflight.gov/essay/Lighter_than_air/Civil_War_balloons/LTA5.htm.

7 Steve Vogel, 'Military Has High Hopes For New Eye in the Sky: Sensor-Equipped Blimps Could Aid Homeland Security', Washington Post, 8 August 2003, B01.

8 Department of Defense Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, '100 Companies Receiving The Largest Dollar Volume Of Prime Contract Awards: Fiscal Year 2001'. www.dior.whs.mil/peidhome/procstat/p01/fy2001/top100.htm.

9 Atlee E. Shidler [ed], Greater Washington in 1980: A State of the Region Report, The Greater Washington Research Center (Washington DC), 1980, pp 6-9.

10 Martin Kady and Mike Sunnucks "'Bandits" Bank on Bush: Federal Contractors Pin Hopes on Defense Boost', Washington Business Journal, 1 June 2001; see www.bizjournals.com/washington/stories/2001/06/04/story1.html (May 15, 2005).

11

Greater Washington Initiative, "Get Regional Facts",

http://www.greaterwashington.org/regional/quick_facts/index.htm.

12 Joel Garreau, Edge City: Life on the New Frontier, Anchor Press, (New York), 1992, pp 6-7.

13 Brent Stringfellow, 'Personal City: Tysons Corner and the Question of Identity' in A. Bingaman, L. Sanders, and R. Zorach [eds], Embodied Utopias: Gender, Social Change, and the Modern Metropolis, Routledge, (New York), 2002, p 174.

14

'Tysons Corner Center: Mall Directory'

http://www.shoptysons.com/searchstore/index.cfm.

15 'US Army Strategic Communications Command Microwave Station, Tysons Corner, VA (Fort Ritchie Site E)', http://coldwar-c4i.net/Site_E/index.html, May 27, 2001 and 'Warrenton Station B', www.fas.org/irp/facility/warrenton_b.htm.

16 National Capital Planning Commission, The National Capital Urban Design and Security Plan, NCPC, (Washington DC), October 2002, pp 6-10.

National Capital Planning Commission, Designing for Security in the Nation's Capital: A Report by the Interagency Task Force of the National Capital Planning Commission, www.ncpc.gov/planning_init/security/DesigningSec.pdf.

17 Maureen Fan, 'Block by Block, Access Denied: Security Just One Reason D.C. Has Moved Beyond L'Enfant', Washington Post, 22 August 2004, A01; see www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A22340-2004Aug21.html.

18 Simson Garfinkel, Database Nation: The Death of Privacy in the 21st Century, O'Reilly & Associates, Inc (Sebastopol, CA), 2000, pp 1-12.

19 'In the Matter of Searches Involving 555 Grove Street, Herndon, Virginia, and Related Locations: [Proposed Redacted] Affidavit in Support of Application for Search Warrant, US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, Alexandria Division, October 2003, www.usdoj.gov/usao/vae/ArchivePress/OctoberPDFArchive/03/safaaffid102003.pdf.

20 Ibid, p 6.

21 Nancy Dunne, 'Attack On Terrorism - US Homefront: US Muslims see their American Dreams Die', Financial Times, 2 May 2002; see http://specials.ft.com/attackonterrorism/FT3P6NEVBZC.html.

22 District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia Advisory Committees to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 'Civil Rights Concerns in the Metropolitan Washington, D.C. Area in the Aftermath of the September 11, 2001, Tragedies: Chapter 2', June 2003, www.usccr.gov/pubs/sac/dc0603/ch2.htm.

23

Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth 1820-2000,

Pantheon (New York), 2003, p 3.

24 National Defense University, Stuart Johnson and Martin Libicki (eds.), Dominant Battlespace Knowledge, NDU Press Book (Washington DC), 1995.

25 ESRI, GIS for Homeland Security, ESRI White Paper, November 2001, www.esri.com/library/whitepapers/pdfs/homeland_security_wp.pdf.

26 Usama Fayyaad, Gregory Platetsky-Shapiro and Padhraic Smyth, 'From Data Mining to Knowledge Discovery in Databases', American Association of Artificial Intelligence: AI Magazine 17, Fall 1996, pp 37-51.

27 Mark Monmonier, Spying With Maps: Surveillance Technologies and the Future of Privacy. University of Chicago Press (Chicago and London) 2002, pp 1-16.

28 Spencer S. Hsu, 'Defense Jobs in N.Va. At Risk: Many Buildings Fall Short of New Security Standards', Washington Post, 10 May 2005, A01; see www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/09/AR2005050901087.html.

29

David Cho, 'Base Plan Undercuts Sprawl Battle: Region's Leaders Criticize Job

Shifts',

Washington Post, 15 May 2005, A01; see www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/14/AR2005051401190.html.

30 Hsu, op cit, A01.